Here are the names of the Irish men who fought with the 7th Cavalry and died either during or shortly after the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Their details are displayed in the following format:

NAME - AGE - RANK - COMPANY - COUNTY - OCCUP - PERSONAL DETAILS

Atcheson, Thomas 41 Private F Antrim Unknown 5' 5¼" in height, hazel eyes, dark hair

Barry, John 27 Private I Waterford Laborer 5'7¾" in height, grey eyes, dark hair, ruddy complexion

Boyle, Owen 33 Private E Waterford Soldier 5'6" in height, grey eyes, dark hair, fair complexion

Bruce, Patrick 31 Private F Cork Unknown 5'7" in height, blue eyes, brown hair, ruddy complexion

Bustard, James 30 Sergeant I Donegal Soldier 5'6½" in height, hazel eyes, light hair, fair complexion

Carney, James 33 Private F Westmeath Unknown 5'4¼" in height, grey eyes, black hair, dark complexion

Cashan, William 31 Sergeant L Queen's County Soldier 5'9" in height, blue eyes, brown hair, fair complexion

Connor, Edward 30 Private E Clare Unknown 5'8½" in height, hazel eyes, brown hair, ruddy complexion

Considine, Martin*28 Sergeant G Clare Unknown 5'7½" in height, blue eyes, brown hair, fair complexion

Cooney, David** 28 Private I Cork Laborer 5'5¾" in height, grey eyes, dark hair, fair complexion

(Promoted Sergeant on June 28th)

Downing, Thomas 24 Private I Limerick Laborer 5'8¼" in height, blue eyes, sandy hair, florid complexion

Drinan, James* 23 Private A Cork Laborer 5'7½" in height, grey eyes, light brown hair, dark complexion

Driscoll, Edward 25 Private I Waterford Laborer 5'6" in height, hazel eyes, light hair, light complexion

Egan, Thomas 28 Corporal E Tipperary/Dublin Laborer 5'5½" in height, grey eyes, sandy hair, light complexion

Farrell, Richard 25 Private E Dublin Laborer 5'8¾" in height, grey eyes, brown hair, fair complexion

Finley, Jeremiah 35 Sergeant C Tipperary Laborer 5'7" in height, grey eyes, brown hair, light complexion

(He made Custer's buckskin jacket.)

Golden, Patrick*26 Private D Sligo Slater 5'9¼" in height, blue eyes, brown hair, fair complexion

Graham, Charles 39 Private L Tyrone Unknown 5'6¾" in height, blue eyes, brown hair, florid complexion

Griffin, Patrick 28 Private C Kerry Unknown 5'9" in height, black eyes, dark hair, ruddy complexion

Henderson, John 37 Private E Cork Unknown 5'7¾" in height, grey eyes, light hair, fair complexion

Hughes, Robert H 36 Sergeant K Dublin Unknown 5'9" in height, blue eyes, brown hair, fair complexion

(Carried Custer's battle standard)

Kavanagh, Thomas G 31 Private L Dublin Farmer 5'11¼" in height, grey eyes, red hair, ruddy complexion

Kelly, Patrick 35 Private I Mayo Unknown 5'5" in height, grey eyes, sandy hair, fair complexion

Kenney, Michael 26 1st Sergeant F Galway Soldier 5'7¼" in height, grey eyes, brown hair, fair complexion

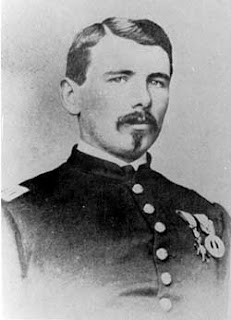

Keogh, Myles W 36 Captain I Carlow Soldier The only Irish-born officer, 2nd-in-command to Custer

Mahoney, Bartholomew 30 Private L Cork Teamster 5'10" in height, hazel eyes, dark hair, sallow complexion

Martin, James* 28 Corporal G Kildare Laborer 5'5" in height, grey eyes, brown hair, fair complexion

McElroy, Thomas 31 Trumpeter E Down Musician 5'5½" in height, blue eyes, dark hair, ruddy complexion

McIlhargey, Archibald 31 Private I Antrim Unknown 5'5" in height, brown eyes, black hair, dark complexion

Mitchell, John 34 Private I Galway Unknown 5'6¼" in height, blue eyes, brown hair, ruddy complexion

O'Connell, David 32 Private L Cork Unknown 5'7½" in height, dark eyes, brown hair, ruddy complexion

O'Connor, Patrick 25 Private E Longford Shoemaker 5'5½" in height, blue eyes, light hair, fair complexion

Smith, James 34 Private E Tipperary Unknown 5'6" in height, hazel eyes, brown hair, ruddy complexion

Sullivan, John*25 Private A Dublin Laborer 5'6¼" in height, grey eyes, brown hair, medium complexion

*Killed with Reno battalion

**Died later of wounds received in the battle